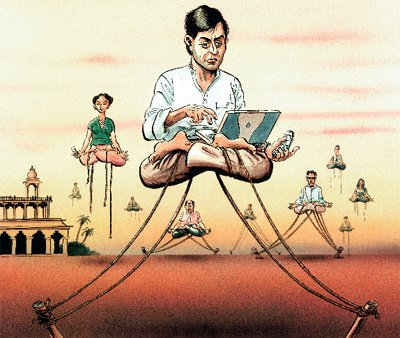

"Each person will become his own Buddha, his own Einstein, his own Galileo. Instead of relying on canned, static, dead knowledge passed on from other symbol producers, he will be using his span of eighty or so years on this planet to live out every possibility of the human, prehuman and even subhuman adventure."

"Each person will become his own Buddha, his own Einstein, his own Galileo. Instead of relying on canned, static, dead knowledge passed on from other symbol producers, he will be using his span of eighty or so years on this planet to live out every possibility of the human, prehuman and even subhuman adventure."Sounds good, except the author of the above quote is none other than Dr. Timothy Leary, and his practice for achieving enlightenment ultimately turned out to be counter-productive. Dr. Leary's theories and experiments on altered states of consciousness relied on external stimulants, and reliance on the external, in effect, is the opposite of becoming your own Buddha, your own Einstein, your own Galileo.

The American psychologist William James once said, "...our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different... We may go through life without suspecting their existence; but apply the requisite stimulus, and at a touch they are there in all their completeness, definite types of mentality which probably somewhere have their field of application and adaptation."

What were the stimuli necessary and sufficient to overthrow the domination of the rational and to open up the other "potential forms of consciousness?" Although Leary acknowledged that Indian philosophers and Japanese Buddhists have described hundreds of methods, William James used nitrous oxide and ether to stimulate the mystical consciousness, and Leary followed that path, leading to his famous experiments with LSD.

"To understand our findings," he wrote, "we have finally been forced back on a language and point of view quite alien to us who are trained in the traditions of mechanistic objective psychology. We have had to return again and again to the nondualistic conceptions of Eastern philosophy, a theory of mind made more explicit and familiar in our Western world by Bergson, Aldous Huxley, and Alan Watts."

At that time, Watts was addressing topics such as personal identity, the true nature of reality, consciousness, and the pursuit of happiness, relating his experience to scientific knowledge and to the teachings of Eastern and Western religions and philosophies. In 1957, he published "The Way of Zen," which focused on philosophical explication and history, but largely ignored the practical aspect of Zen, that is, the practice of zazen. In "The Book - The Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are," he criticized "our tacit conspiracy to ignore who, or what, we really are."

Briefly, his thesis was that the prevalent sensation of oneself as a separate ego enclosed in a bag of skin is a hallucination which accords neither with Western science nor with the experiential religions of the East. This hallucination of a separate ego self "underlies the misuse of technology for the violent subjugation of man's natural environment and, consequently, its eventual destruction."

In the early '60s, he began to dabble with psychedelic drugs, initially with mescaline and later LSD with various research teams at UCLA. Watts' books of the Sixties reveal the influence of these chemical adventures on his perception of the separate ego self. In 1962's "The Joyous Cosmology," he asks,

"Is it possible, then, that Western science could provide a medicine which would at least give the human organism a start in releasing itself from its chronic self-contradiction? The medicine might indeed have to be supported by other procedures - psychotherapy, "spiritual" disciplines, and basic changes in one's pattern of life - but every diseased person seems to need some kind of initial lift to set him on the way to health... Is there, in short, a medicine which can give us temporarily the sensation of being integrated, of being fully one with ourselves and nature as the biologist knows us, theoretically, to be? If so, the experience might offer clues to whatever else must be done to bring about full and continuous integration. It might be at least the tip of an Ariadne's thread to lead us out of the maze in which all of us are lost from our infancy."And therein can be found the problem with his and Leary's inquisition into psychedelics as a way of self realization: the answer to understanding the self can never be found outside of the self, but only within. The Indian philosophers and Japanese Buddhists acknowledged by Dr. Leary, as well as the Buddha himself, were quite clear about this. There is nothing external to be sought, we are complete and whole, lacking nothing - perfect, immaculate. To seek a drug as a "medicine" to realize this assumes that something "out there" is required, and thus the seeker is off in the wrong direction, moving further from realization, not closer.

Back in the '70s, as the psychedelic culture of the previous generation began to self destruct, I would occasionally hear people say things like, "Oh, I don't need to use drugs anymore. I just practice meditation." Statements like that led me to assume that the experience of zazen was somehow similar to that of getting high. Of course, nothing could be further from the truth. What these people were saying, in effect, was, "I've stopped looking outside of myself for answers. Now, I just look within."

We are all already our own Buddha, our own Einstein, our own Galileo, and when we finally use our own efforts and resources to see through the illusion of the distinction between self and others, one is then living out "every possibility of the human, prehuman and even subhuman adventure."