In 1979, Miller Beer opened a new brewery on the grounds of the former Turner Air Field near Albany, Georgia. A year later, Albany's Radium Springs went dry. That's why I live in Atlanta today.

Allow me to connect the dots for you.

Back in the 1970s, I was a geology undergrad at Boston University. This was after the energy crisis and the OPEC embargo of the early '70s. Petroleum companies ruled the geology world and I fully expected that my post-graduation career would involve employment at one oil company or the other, out sitting by a West Texas oil rig logging the cuttings before being moved to some cubicle in Houston or Denver to analyze maps. Corporate recruiters from Exxon and Mobil had already visited campus and some of the best and brightest of the grad students already had contracts to join the companies after graduation.

But the one problem was that I didn't much care for the petroleum geology professor. It was nothing major - he wasn't a creep or anything and hadn't abused me or any of my fellow students (as far as I knew) but he just seemed to me kind of stuffy and off-putting. I still took a couple of courses under him, but I much more enjoyed the teaching style and the presence of the professor who taught glacial geology.

Dr. Caldwell's first name was Dabney but he hated that name - he went by Dee and even his students called him that. His father was the Georgia writer Erskine Caldwell, author of Tobacco Road and God's Little Acre. Graduate students advised us undergrads to never talk to him about that. Apparently, after movies were made of Tobacco Road and God's Little Acre, Erskine Caldwell moved to L.A., went Hollywood, divorced Dee's mother, and lost interest in his children. Dee hated his Dad for that and didn't want to talk about him. I never brought the subject up with him.

One of the best parts of geological pedagogy is field trips. Geology is a field science and it's one thing to talk about rocks and formations in the classroom, but one ultimately has to go out and see, touch, and experience them for oneself. In practical terms, this meant that many weekends in the early autumn and late spring, before and after the cold New England winters covered everything with snow, one prof or the other would pile a bunch of students into one or more of the University's passenger vans and we'd drive off to look at the limestones of upstate New York, granites and other plutonic rocks of New Hampshire, or dinosaur footprints in the Connecticut River Valley.

In my experience, Dee led the best field trips, usually up to Maine to examine the glacial deposits he had studied for his own doctorate and for his continuing academic research. I learned a lot, but we were also young, 20-something college students, and those academic field trips also involved a lot of exuberant late-night partying, beer drinking, and romantic intrigue. We went to great lengths to hide these extracurricular activities from most of the other professors, and most of the other professors went to great lengths to maintain plausible deniability of the extracurriculars they of course knew were occurring. They'd stay in hotel rooms while we were out camping around roaring bonfires.

But Dee maintained less of a wall separating us from him than did the other profs. Thankfully, he didn't get involved in the romantic intrigue, although his partner was an ex-grad student just a few years out of school herself. But more than a few times, he'd join us for beers around the campfire and knock back swigs of Jack Daniels from the bottle being passed around. On one particularly raucous night, we all started singing Onward Christian Soldiers, of all things, as Dee led us by a Coleman lantern raised high on a march through the woods. When we came to a pond, we kept on marching as Dee led us first into knee-deep water, then up to our waist, then up to our shoulders. We kept on singing until Dee was literally in over his head and all we could see was the light of his lantern still held aloft.

The petroleum geology professor would never have done that.

In addition to glacial geology, Dee also taught hydrogeology - the study of surface- and groundwater. In New England, the plentiful glacial deposits are the principal groundwater aquifers, so the association of the two disciplines is logical. In 1979, the same year Miller was opening its Albany brewery, I signed up for Hydrogeology 101.

During the first lecture on the first day of the first course in the sequence, Dee told us how lucky we all were to be there. Hydrogeology, while not exactly an exotic study, was still not widely taught at most geology programs but, Dee advised us, water resources will become increasingly scarce and experienced groundwater hydrogeologists will become increasingly in demand. The Golden Age of Oil Exploration was already coming to a close, he advised, but hydrogeology will be the Next Big Thing. "In a few years, you may well find yourselves as experienced hydrogeologists at a time when demand for the science is at an all-time peak."

It sounded like a boast and needless self-promotion as we were already there, signed up for the course, but it turns out Dee was right.

When Radium Springs went dry, many god-fearing residents of Albany, Georgia blamed it on the good Lord's vengence for opening a brewery in the Bible Belt. They demanded that the brewery be shut down before god's wrath manifested itself in yet more painful ways.

Politicians were caught in a bind - they didn't want to go up against the big-money interests of the Miller Brewing Company on the one hand but didn't want to appear to be ignoring the will of the more religious of their constituents on the other. So they did what any good politician would do - they commissioned a study of the problem.

The Governor's Accelerated Groundwater Program was initiated in 1980 as a comprehensive study of the state's hydrologic resources and to develop recommendations for proper management thereof. But it turns out that there weren't a lot of experienced groundwater hydrogeologists in Georgia to study the problem, so a call went out to recruit qualified experts to the Georgia Geological Survey.

You've already connected the dots, I'm sure, but one day my telephone rang (this was long before the internet and email) and the secretary of BU's Geology Department told me that an alumnus working down in Georgia had called Dee, his old professor, asking about recent graduates he could hire for the Accelerated Groundwater Program. I was teaching high-school Earth Science at the time, not my dream career, and Dee recommended me. I took the job and moved to Atlanta, and fast forward, here I am, 43 years later, still living in Georgia.

I worked at the Geological Survey for only three years, but with that experience under my belt, I took a job at an Atlanta-based national engineering and environmental consulting company for whom I worked at sites all across the country for the next 20-odd years. The last 10 years of my career before retirement were at various smaller firms.

Dee was correct - groundwater became the dominant field of employment for geologists. Since the late 1980s, the majority of geology graduates were suddenly all hydrology majors, but I was fortunate enough to always have had a few more years of experience in that field than 95% of my colleagues. Those best and brightest grad students who were recruited from grad school by the oil companies found themselves laid off in the1980s. I found myself interviewing them for employment - not the actual BU grads I knew, but similar graduates from other programs who couldn't believe that they were on the applicant side of the desk despite all their petroleum experience and I, a mere hydrogeologist, was on the other.

"Look, I'll just come out and say it," one once told me in an interview, "the work I did in the oil industry was far more scientific and complicated than anything you do in the environmental field, and any lack of experience on my part in your business won't be a problem for me at all." I didn't hire him, not because of his arrogance or because I was offended by what he said, but because his statement told me that it would be difficult if not impossible to train him in new things.

Anyway, it turns out Radium Springs didn't go dry because of god's wrath or even over-pumping by Miller Brewing. The Miller Brewery tapped a deeper source, the Clayton-Claibourne Aquifer, than the Principal Artesian Aquifer that fed Radium Springs. Hydrologic studies showed that the prolonged drought of 1979 and 1980 led to lower water levels in the Principal Artesian Aquifer, and sure enough, once the drought ended, the flow of water returned to the spring. Ironically, the historic Radium Springs Casino (not a gambling casino, but more of a resort) shut down in 1994 after prolonged rainfall flooded the facility.

Dee Caldwell passed away in 2006.

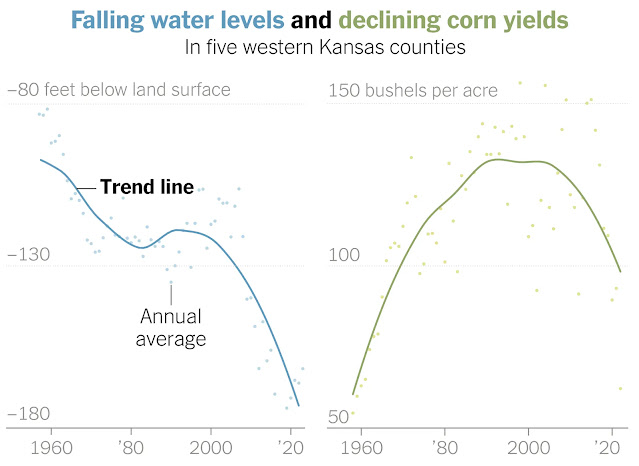

A headline article in the New York Times today talked about how groundwater resources are being depleted at alarming levels across the U.S., and how little is being down to manage or preserve our remaining reserves. The graph up above is from that article. I sat down to write about that, but an old man gets lost in memory and nostalgia and instead I wound up writing this memoir.

The Universal Solar Calendar calls today "Listening," and as I wrote this, I listened to new (2023) releases by the bands Horse Lords, Ratboys, and bar italia, and, of course, the posthumous release by the late jaimie branch.

No comments:

Post a Comment