An article in the NY Times today about Marshall Allen's struggle to keep the Sun Ra Arkestra going made me think of the profound influence music has had on my life. I have been listening to Sun Ra's music for some three decades now, basically since I first discovered jazz in the 1970s. The musical road that led me to Sun Ra, and the effect of that discovery, says a lot about me.

Growing up, I was, of course, a fan of your basic 60s rock and roll - the Beatles and the Stones and the Top 40 pop sounds on A.M. radio, specifically, 77 WABC out of New York. The Top 40 then was a much more varied patchwork of styles and genres than it is now, and within an hour, one could hear the current single of any one of the British Invasion bands of the 1960s, West Coast bands like the Jefferson Airplane and the Doors, pop bands like Three Dog Night and Creedence Clearwater, and any number of novelty songs ("They're Coming to Take Me Away, Ha, Ha!"). But around 1968, something happened that changed my life in a subtle but significant way - my transistor AM radio broke, and I was forced to listen to my parents' F.M. radio.

This radio was in the kitchen and main purpose was to provide classical music while dinner was being prepared and served. But bored and restless, I started tuning up and down the dial in search of my Top 40 hits, and like poor amputated Jenny in Velvet Underground's "Rock 'n' Roll," one fine morning I found a New York station and couldn't believe what I heard. WABC F.M. was playing the Beatles, but not the singles; instead they were playing those other cuts on the albums that weren't getting airplay on the A.M. radio. And beyond the Beatles, they were also playing cuts off of other albums by bands like Buffalo Springfield, Steppenwolf, the Yardbirds, Cream and the Animals. It was as if by going from WABC A.M. to WABC F.M., I had graduated to a more interesting, more exciting level of music. Most of my friends were still content listening to their A.M. pop favorites, which I too still enjoyed, but my appreciation was now guided by a deeper understanding.

Since my initial musical foray over to the F.M. dial had been so rewarding, I continued my adventures in F.M., searching up and down the radio for other stations, and soon found WNEW New York. WNEW was to WABC-F.M. what ABC-F.M. was to ABC-A.M. WNEW was not only playing all of the album cuts by the bands listed above, but also music by bands that never had a Top 40 single, like the Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin and Iron Butterfly. The music was more powerful, rocked harder, and most noticeably, profoundly stranger than anything I had been listening to before.

In fact, the music was so strange, that my friends, ears still glued to the Top 40, dismissed my new tastes. They made fun of me for listening to "weird music." But I didn't care - I found my new music so compelling, so interesting and so essential, that I ignored their taunts and teases, and that marked a turning point for me; specifically, that my musical tastes were now non-conformist, and music was no longer a shared and common bond between my friends and peers and I.

My adventures, now solo, continued. As innovative and eclectic as WNEW was, they still weren't playing some other bands that I had heard or read of, but not yet experienced, such as Pink Floyd or Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. So at this point, to see how much further I could go, I abandoned even my trusty F.M. radio stations as my guide and started listening to new and challenging records on my own.

The pattern soon became that whatever artist, however daunting their reputation or first listen might be, soon became commonplace to my ears, and I searched further and further for something truly mind-blowing. But it seemed that the music of Frank Zappa was on a quest similar to my own - each successive Mothers' record was exploring new territory, from bizarre permutations of rock, to intricate and sophisticated orchestral arrangements, to avant-garde, free-form noise.

This journey from the Beatles' "I Want to Hold Your Hand" to Zappa's "Prelude to an Afternoon With a Sexually Aroused Gas Mask" took place over several years, and over those years, say 1967 to 1973, music changed, the times changed and I certainly changed. Sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll were a given, the A.M. Top 40 radio format had been all but abandoned except by the most unadventurous minority, and my friends were all claiming that they'd always been into whatever group I had discovered, and subsequently abandoned, years earlier. But the non-conformist impulse, first developed years ago listening to my parents F.M. radio in the kitchen, compelled me to discard anything that became too popular, and to keep searching.

At this point, I had nothing but my own instincts to guide me - radio was strictly commercial, the press outdated and passe, word-of-mouth unreliable. I would comb through record stores, used music shops and flea markets looking for something, anything, new and different.

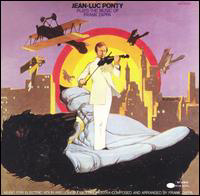

One day, in a railroad salvage store, I came across a recording titled "King Kong - Jean-Luc Ponty Plays the Music of Frank Zappa." It was clearly marked as a "jazz" record. This did not daunt me, since at the time I was already listening to some jazz-rock fusion, like John McLaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and enjoyed some of the jazzier explorations of bands like Traffic and, of course, Zappa. I bought the record, took it home and played it, and instantly loved it. This, I decided, opened up a whole new realm - jazz. Rock was starting to enter the moribund era of the 70s, power ballads, art rock and finally disco, and I wanted no part of it. Jazz on the other hand, represented a whole new world to explore - a fifty-year recorded history, a plethora of styles, and a challenging and adventurous avant garde. I abandoned rock and jumped into jazz with relish.

My first couple months as a jazz fan were mostly exploratory, listening to as many different artists as I could, but my old impulse to find how far I could go in any direction soon kicked in. If I liked, say, Miles Davis' "Kind of Blue," I worked my way to "Bitches' Brew" and on to "On the Corner." Coltrane's "A Love Supreme" would lead me to his later recordings like "Ascention" and "Interstellar Space." But since Coltrane had died in 1967, to go further I had to listen to his successors, like Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp and Albert Ayler.

But as much as my heart, soul and intellect loved and responded to the furious atonal squonk and squeal of this dissonant music, I knew of almost no one who could even be in the same room when some of this music was playing. My non-conformity had graduated to the antisocial.

No matter how extreme or avant garde each artist I listened to was, however, there was always one figure who always sounded "one step beyond" - Sun Ra. Sun Ra seemed to be to jazz what Frank Zappa had been to rock - always ahead of the pack, and constantly searching, expanding and innovating, so the only thing possibly more adventurous than a Sun Ra recording was another Sun Ra record - there was no going beyond Sun Ra, because he was constantly going beyond himself.

How can one even start to describe Sun Ra? He claimed to be from Saturn and dressed that way, played music that alternated free improvisations and outer-space chants with eccentric versions of swing tunes, and lead a big band, called the "Arkestra," that wore exotic costumes, featured dancers, magicians, fire eaters, light shows, and anything else they could dream up. Song titles, "Space Is the Place," "Rocket Number Nine Take Off for the Planet Venus," "Love in Outer Space" can only hint at the cosmic weirdness of the music. Like Frank Zappa, it was often hard to take his music seriously, and an element of humor was laced throughout the entire conceptual package. However, where Zappa eventually degenerated into parody and satire, Sun Ra maintained the single image - jazzman as enlightened alien - throughout his life.

I found the first Sun Ra record I bought, Impulse's "Astro-Black," difficult to listen to, even to my adventurous ears. But around 1974, I saw my first Sun Ra concert and "got it." It all came together in concert - the extended electronic solos, the dancing, the energetic horns, the percussion, the whole ancient-Egypt-meets-science-fiction mentality.

I would see Sun Ra every chance I could get. One interesting thing I noted, though, was that anyone I would take with me to one of these shows enjoyed it almost without fail. They still couldn't listen to my Art Ensemble of Chicago records with me, but watching the spectacle of the Arkestra in full swing, they could not help but be entertained. I had found the antidote to my antisocialness.

One day in New York City, as I was taking the subway, the doors opened and out walked Sun Ra, still dressed in cosmic costume, surrounded by four or five similarly dressed associates. I did not know what to do other than a full prostration right there on the subway platform. Sun Ra, slightly embarrassed, acknowledged my tribute but went on his way.

In the late 70s, he played a week-long gig at Boston's Orpheum Theatre while I was a student at Boston U. I caught two or three of the shows, each night completely different than the show before, and each featuring a gigantic light installation behind the band. That week, while coming out of a movie theatre after seeing the Donald Sutherland remake of "Invasion of the Body Snatchers," I met Sun Ra again in the lobby. We both had attended the same matinee! This time I greeted him by merely shaking hands, and asking if there were body snatchers on Saturn (he assured me there weren't).

Sometime in the 1980s' while I was living upstate New York, I drove to Northampton, Massachusetts and saw one of his later performances. Sun Ra had suffered a stroke, and had to be carried on stage in a chair by the band. Now, Sun Ra was a large man, and jazz musicians, particularly dancing avant garde jazz musicians, aren't notoriously muscular, and it took several band members to carry him onstage. But despite his physical limitations, the show was still strong and exciting and creative.

Several years ago, after Sun Ra's second and fatal stroke, I saw the Arkestra again at the Variety Playhouse in Atlanta's Little Five Points. The Arkestra, now led by Marshall Allen, probably averaged in the 60s in age, but still could blow the roof off. "Those old men can really rock," Beth, my girlfriend, noted. But even with the dancers, the chants, and the solo improvisations, Sun Ra's absence left a profound gap.

Mr. Allen is now having a hard time keeping the Arkestra together and finding a sufficient number of gigs to maintain the house in Philadelphia Sun Ra moved the band into in the 1970s. And Mr. Allen himself is now elderly, and other long time Arkestra members, like the great tenor saxophonist John Gilmore, are now dead. It will be sad to see the presence of this dynamic force pass into the historical legacy of the jazz avant garde.

No comments:

Post a Comment