This is a classic demagogic tactic – to put words in the mouth of your opponents and then attack them for statements they never made. Carcinogenicity was not the basis for banning DDT. Crichton is correct that DDT has not been proven to be a human carcinogen. However, that was not the basis for its ban. DDT was banned in 1972 due to its effects on bird reproduction, especially raptors such as bald eagles and peregrine falcons, which lay eggs with thin shells that often break before hatching when exposed to relatively low concentrations of DDT.

The environmental science behind DDT and its fate and transport, and its effects on receptors, are somewhat complex. This is unfortunate, because it both prevents an easy understanding of the processes involved, and also because it allows one or two individual facts, taken out of context of the whole process, to suggest false conclusions.

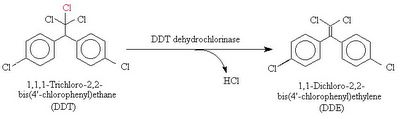

DDT, and especially its degradation product DDE, build up in plants and in fatty tissues of fish, birds, and other animals. As a results, DDT and its degradation products accumulate through the food chain, with apex predators such as raptors having a higher concentration of the chemicals than other animals sharing the same environment.

When present at comparatively low levels, DDE (not DDT) prevents normal calcium deposition during eggshell formation, and causes some species of raptors to lay eggs with thin shells that often break before hatching. Other species are relatively unaffected; for example, the chicken continues to produce normal eggs despite high levels of exposure. However, DDT has been cited as a major reason for the decline of the bald eagle in the 1950’s and 60’s, which was of particularly symbolic interest in that the eagle is the U.S. national bird.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) addressed toxic contamination of the food chain and led to the banning of the widespread use of DDT as a pesticide. But even more importantly, the book popularized the idea in the West that all life-forms are interdependent.

Jonathan Schell’s The Fate of the Earth (1982) and Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature (1989) addressed different global environmental problems - the worldwide consequences of nuclear proliferation and the impact of global warming. Their warnings led to major changes in national and international policy: the START treaties that negotiated nuclear arms reduction agreements between the United States and the Soviet Union, and the Kyoto agreements to cut carbon dioxide emissions. But as Donald Swearer of Swarthmore College points out, each of these books shared a similar holistic worldview, namely, as the 1975 National Academy of Sciences Report stated, that our world is a whole “in which any action influencing a single part of the system can be expected to have an effect on all other parts of the system.”

In Buddhism, this holistic worldview is expressed metaphorically in the image of Indra’s net - the concept of the universe as a vast web of many-sided jewels, each constituted by the reflections of all the other jewels in the web and each jewel being the image of the entire universe. This principle of interdependence integrates all aspects of the ecosphere in terms of mutual codependence. Individual entities are by their very nature relational, thereby undermining the dualistic concept of an autonomous self versus the “other,” be it human, animal, or vegetable. Such a worldview represents a rejection of the dominance of one human over another or humans over nature, and is the basis of an ethic of compassion that respects biodiversity.

In the view of the Thai monk Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, “The entire cosmos is a cooperative. The sun, the moon, and the stars live together as a cooperative. The same is true for humans and animals, trees, and the earth. When we realize that the world is a mutual, interdependent, cooperative enterprise . . . then we can build a noble environment. If our lives are not based on this truth, then we shall perish.”

A Western observer, noting that the term dharma not only refers to the teachings of the Buddha but also to all things in nature, characterizes Buddhism as “religious ecology.”

Master Dogen wrote, “The sutras [i.e., the dharma] are the entire universe, mountains, and rivers and the great wide earth, plants and trees.” Swearer notes that Dogen’s view can be used as support for the preservation of species biodiversity.

No comments:

Post a Comment