Oh, dear - I can see that this mapping and story-telling is going to take a lot longer than I had anticipated. It's already been almost a week, and I'm not even half-way through the story of the Buddha's life. I expected to be past the bio by the fourth entry (my plan was after an initial introductory post, to warn against attachment to the teacher by the second and then to cover the whole story of the Buddha's life and enlightenment in a single post; now here it is the third of the biographical postings, and we haven't even gotten to his enlightenment yet).

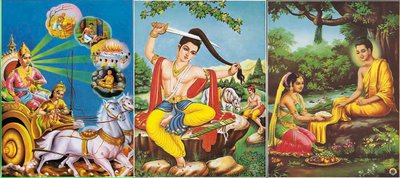

Oh, dear - I can see that this mapping and story-telling is going to take a lot longer than I had anticipated. It's already been almost a week, and I'm not even half-way through the story of the Buddha's life. I expected to be past the bio by the fourth entry (my plan was after an initial introductory post, to warn against attachment to the teacher by the second and then to cover the whole story of the Buddha's life and enlightenment in a single post; now here it is the third of the biographical postings, and we haven't even gotten to his enlightenment yet).Anyway, the story so far is summarized by the little triptych I've assembled above - after observing human suffering in the form of poverty, sickness, old age and death, and seeing wandering monastics struggling to find a meaning to life (first pic), he decides to leave home and ritually cuts his hair to become an ascetic himself (pic two), almost dying on the process before he is saved and renourished by a passing goat-herder's daughter (third pic). See how quickly I can move through the story with a little motivation and visual assistance?

Anyway, having now rejected the comfortable and luxurious life of a prince, and the other extreme of asceticism and its austere practices, Siddhartha Gautama decided that there had to be a Middle Way between these two extremes. Neither extreme had given him any insight on the cause of the human suffering which had affected him so greatly, not to mention how that suffering could be ended.

By the way, the five mendicants, his ascetic buddies from his former practice, were so disappointed by his actions, taking food and so on, that they rejected him and resolved never to speak to him again; they kicked him out, as it were, of their little circle of friends.

Regardless, once his health was renourished, he continued in his practice alone, and one day he sat down under a ficus tree and resolved to sit in meditation until he had an answer. To our contemporary minds, used to our comforts and luxuries, extended sitting may sound like an austerity, but after what he had been through, this appeared to Siddhartha to be the Middle Way.

Can you imagine the state of mind he must have been in? He had left home and gave up everything he had - his royalty, his wife and his son, and taken on a life of extreme hardship only to discover that there was no answer there either. Unlike those of us who might resolve to sit for an hour a day, or even for a week of 14-hour periods, I believe he was ready to die under that tree if no answer presented itself to him first. Total commitment. No turning back.

And this, of course, is the pivotal point of the whole story, and one of the single most important moment in all of Buddhism (second only, of course, to your enlightenment). Stories and legends vary on how long he sat there, and exactly what happened. All I can say is - I don't know.

The hardest three words to say, sometimes. I wasn't there, and even if I was, I wasn't inside of his head. And I have not had the same experience of total and supreme enlightenment (annutara samyak sambodhi). The best that I can do is repeat the tales and complete the story in roughly the manner that it has been passed down, along with all its allegories and legend.

As Siddhartha went deeper and deeper into meditation, and gained increasing clarity of mind, suffering appeared to him to be a fundamental human condition, caused by our cravings, desires and attachments. It was also apparent to him that by ending these cravings, desires and attachments, we could also end our suffering. Of course, the issue was how do we end the cravings, etc. and break free from suffering?

And, the story goes, as he progressed further down this meditative path, his own ego-self appeared before him. First, it manifested itself as seductive singing maidens (think "the Sirens" from the Odyssey), luring him from his meditation back into the world of longing and desire. When that was not successful, his ego then refigured itself into the form of the god Mara - a fierce and fearsome figure, commanding him to stop this practice immediately upon threat of death. Mara raged and snorted fire and summoned up huge armies, and demanded that Siddhartha was not worthy of enlightenment and that he, Mara, should rightfully have that experience.

But Siddhartha refused to be distracted. Touching the earth with a single finger to reaffirm his connection with the here and now, he saw the vision even of Mara melt away, and by dawn, when the morning star rose over the horizon, Siddhartha Gautama had the direct realization of enlightenment. This was not an intellectual achievement - it would be a gross understatement to say "he figured it out," but a direct, intuitive, experiential awakening. We don't "figure out" how to awake from a dream, we just awaken, and similarly, the Buddha did not "figure out" enlightenment - it came to him, not he to it.

"How marvelous," he later said he thought at that moment. "I and all sentient creatures have come to enlightenment together." For in his mind, there was no separation between himself and all others - not only humans but all sentient beings, even the minds of trees and grasses. If he had thought for a nanosecond, "I have become enlightened," that conceptualization of "I" would have separated him from all other beings, and he would not have achieved enlightenment as surely as if here were to have stepped aside for his Mara (ego-self) manifestation.

In his mind, the whole universe had achieved enlightenment, not only in the present moment, but in the past and the future as well. In his mind, you had awakened, I had awakened, we all had awakened - there was no difference. Of course, it may not feel this way to us - I certainly don't think of myself as a fully enlightened Buddha - but that is what Sakyamuni Buddha taught.

And it is that disconnect between this teaching and our own experience that gives rise to the Great Doubt that arises and is cultivated in Zen practice.

No comments:

Post a Comment