Sunday in New York: after helping myself to the hotel's complimentary breakfast, I hopped on the Q train to Brooklyn in order to attend the Sunday morning services at the Zen Center of New York (Fire Lotus Temple). Services started at 9:30, a refreshing and rational change of pace from the Atlanta center's 7:30 and Sanshin's ghastly 4:00 am.

Sunday in New York: after helping myself to the hotel's complimentary breakfast, I hopped on the Q train to Brooklyn in order to attend the Sunday morning services at the Zen Center of New York (Fire Lotus Temple). Services started at 9:30, a refreshing and rational change of pace from the Atlanta center's 7:30 and Sanshin's ghastly 4:00 am.Today marked the first day of the Center's ango, an extended (in this case, 12 weeks) period of intensified practice. During ango, everyone kicks their practice up a notch, with longer sitting periods, more frequent attendance at services, more sesshins, etc. To start the ango, Fire Lotus had a mondo (question and answer) rather than a typical dharma talk. The topic was generally the obstacles we face to our practice - do we use the 24 hours of a day, or do the 24 hours use us?

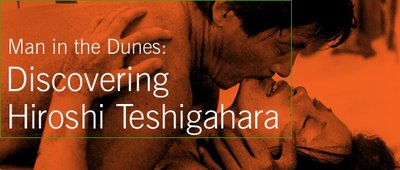

As long as I was in Brooklyn, I went over to the Brooklyn Academy of Music for a little Japanese cinema. The BAMCinematek was hosting a film series entitled "Man in the Dunes: Discovering Hiroshi Teshigahara." A sculptor, painter, opera director, interior designer, writer, and more, it was Teshigahara's film career that brought him international recognition. His diverse artistic background and collaboration with Japan's brightest artists resulted in thought-provoking films that destroyed the traditional boundaries of Japanese cinema.

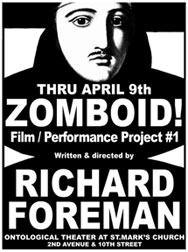

Today's screening was The Face of Another (1966), a Bergman-esque film about a man who becomes horribly disfigured in an accident, leaving his face covered in bandages and his wife unable to look at him. He receives an artificial face to wear that differs from his own, which Teshigahara exploits to explore the loss of identity. The movie also follows a parallel story about a young woman, half of whose face is horribly scarred by radiation poisoning from Nagasaki, who drowns herself after an act of incest with her brother. Reminiscent of Bergman's Persona, including the famous melted-film-cell scene, the movie is a sort of psychological Frankenstein story filled with symbolism, flamboyant cinema technique and unsettling imagery.Later, I had theater tickets again. Now, I know I called last night's performance of Fatboy "avant garde," but Richard Foreman reminded me what "avant garde" really meant. Fatboy was, at best, post-modern, but avant-garde it wasn't.

Today's screening was The Face of Another (1966), a Bergman-esque film about a man who becomes horribly disfigured in an accident, leaving his face covered in bandages and his wife unable to look at him. He receives an artificial face to wear that differs from his own, which Teshigahara exploits to explore the loss of identity. The movie also follows a parallel story about a young woman, half of whose face is horribly scarred by radiation poisoning from Nagasaki, who drowns herself after an act of incest with her brother. Reminiscent of Bergman's Persona, including the famous melted-film-cell scene, the movie is a sort of psychological Frankenstein story filled with symbolism, flamboyant cinema technique and unsettling imagery.Later, I had theater tickets again. Now, I know I called last night's performance of Fatboy "avant garde," but Richard Foreman reminded me what "avant garde" really meant. Fatboy was, at best, post-modern, but avant-garde it wasn't. Foreman and his Ontological-Hysteric Theater Company have been putting on shows in New York since 1968, but this evening's show expanded his already broad horizons by incorporating film into the performance. In 2004, the Ontological-Hysteric Theater began "The Bridge," an international media and performance collaborative, through which Foreman and longtime collaborator Sophie Haviland film performances at Universities and Arts organizations throughout the world. This evening's performance consisted of screenings on two walls of what I assume was various Bridge projects, with five performers acting, and interacting with the film, on stage.

The amazing thing was: I got it. Foreman is entering the same realm through artistry that Zen has mastered though practice.

Our conscious minds are forever trying to entertain themselves, and lean toward the informative, the amusing and the pleasant, and lean away from the boring, the uninformative, and the unpleasant. The practice of zazen largely is about overcoming this tendency - the mind rebels against just sitting and staring at a wall. The first objection I hear from most people about practice is "It sounds boring." But when we overcome that barrier and learn to accept the "dull" and the "boring," other objections arise, and soon we find ourselves peeling successive layers off of the onion as we get to the real "self" within.

In his program notes, Foreman writes "I propose that every compositional strategy (formalist, narrative, etc) is a distortion of reality, a relative lie - a limitation of options. Every choice closes down most of the world (all other alternatives). Yet a certain amount of choice and compositional procedure cannot be avoided (but do try!). Of what remains - make the lie evident as a lie. Radical choice: make the stage event in a certain sense 'unconvincing.'"

Foreman is probably the most honest director in theater. Most plays, even Fatboy with its postmodern self-references, rely on a certain amount of suspension of disbelief, and try to "fool" you into thinking that what's on stage is, in fact, real. Foreman turns every theater convention of its ear to remind the audience that they are sitting in a theater watching performances on a stage. The lights were turned around so that they shined from the stage into the audience. The performers, four attractive young women and one man, behaved in an extremely artificial manner, never attempting to create a suspension of disbelief. Everything about the performance reinforced the true reality of the moment: an audience sitting in seats watching performers interact with film, recorded sounds and lights.

This "tossing away" is a precise artistic corollary to the "peeling of the onion" that occurs during zazen. As we toss away our rejection of the "boring," our fantasies, our memories, our prejudices and our preferences, something different starts to emerge - our true nature, untainted by our minds.

"Zomboid," then, was an exercise in pure theater for the sake of pure theater, with no narrative, no rational statements, no theme, no moments of clarity for the mind to latch on to. Through a variety of techniques, Foreman stayed honest and in the moment - no one, not the sound technician (Foreman), the lighting director (Foreman again), the performers ("actors" would not be an accurate or honest term) or the audience ever forgot their exact role in the moment.

"We humans understand, finally, only those illusionary systems that we 'construct' for ourselves (the social contract)" Foreman writes. "We are blind to the complex 'whole' that operates outside (below and above) our consciousness."

How Zen is that?

Walking into the box office to pick up my tickets, I was shocked to see Foreman himself standing in the lobby, chatting with friends. No backstage-shrinking prima donna he, he was unpretentiousness, real and in the moment.

How Zen is that?

No comments:

Post a Comment