A lot has already been said and written about the newly-released recording of this 1957 session, so instead of repeating what's already been stated, allow me to provide some excerpts from the best review that I've seen to date:

A lot has already been said and written about the newly-released recording of this 1957 session, so instead of repeating what's already been stated, allow me to provide some excerpts from the best review that I've seen to date:Critic's Notebook

December 21, 2005

Jazz Gem Made in '57 Is a Favorite of 2005

By Ben Ratliff

The New York Times

". . . [Many people] believe, or have heard, that jazz crinkled up and collapsed after Coltrane. That the musicians have defaulted on audiences, going deep into their own heads instead. That there's been no successor, because Coltrane broke the mold, threw away the key, set the bar too high, stretched the envelope as far as it would go, established a holding pattern, and other truth-obscuring clichés.

. . . There are a lot of great jazz musicians in New York, and in the world. But the number of great and economically sustainable bands has declined, along with an international audience and a circuit of clubs that encourages those bands to feel a sense of competition, and opportunities for those bands to play repeatedly for regular audiences in the same small places. A. J. Liebling once wrote that French food declined after World War I with the rise of highway driving, since small restaurants weren't committed to satisfying the same clientele night after night. Instead, they could serve the same dishes and not worry about improvement; regular waves of new diners would chew away, unaware of the stasis. In a way, the same goes for jazz. . .

Monk and Coltrane played as many as 75 nights within a five-month stretch at the Five Spot Cafe in the East Village. The Coltrane Quartet played 14 weeks at the Half Note in the span of a year, from spring 1964 to spring 1965. Fourteen. It was a different time in many ways: it seems that anytime I meet someone who saw either of those bands at those clubs, they won't say that they went once, as if to cross it off a list; they went twice or three times a week, as part of their lives. (No Internet. No TiVo. Cheap rent. No risk of being thought a loser if you liked to go to jazz clubs at night.)

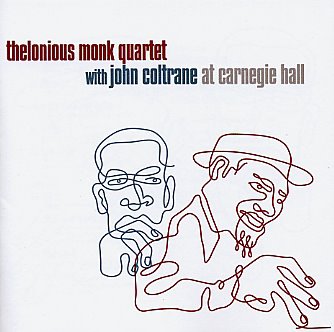

Monk's quartet with Coltrane recorded three songs in the studio in summer 1957, at the beginning of that band's short existence. They can be heard on "Thelonious Monk With John Coltrane." They're very good, and they contain a newly advanced Coltrane. But they are dry-runs when set next to the 51 minutes from Carnegie Hall, which were discovered for the first time in January.

The Carnegie tape comes from late November 1957, after five rigorous months of Five Spot gigs, toward the end of the band's six-month life. (Very little taped material of this band in that year at the Five Spot, and with low fidelity, is known to exist.) On the Carnegie album the band is relaxed, limber, magnetic; the tempos are more wakeful. Compare the tune "Nutty" between the studio and stage versions, and you will hear it quickly. Coltrane has become agile, finding a flexible way of running his original patterns. Monk balances an inscrutable serenity against driving, almost violent figures. And everything coming from Shadow Wilson, the drummer, is to be savored: he guards and upholds the groove, while building small, richly detailed accents around it.

But the band ended a little more than a month later, and contractual issues between Coltrane and Monk's record labels made it impossible for them to record again. We're lucky to have this. . .

This is how jazz works. It is not a volume business. (Its essence is the opposite of business.) Its greatest experiences are given away cheaply, to rooms of 50 to 200 people. Literature and visual art are both so different: the creator stands back, judges a fixed object, then refines or discards before letting the words go to print, or putting images to walls. A posthumously found Hemingway novel is never as good as what he judged to be his best work. But in jazz there is always the promise that the art's greatest examples - even by those long dead - may still be found."

No comments:

Post a Comment