Soma was the mass-produced narcotic-tranquilizer in Aldous Huxley's

Brave New World. In the 1932 novel, this "opiate of the people" is regularly taken by all members of a peaceful high-tech society of the future in order to produce feelings of euphoric happiness, and replaces religion and alcohol.

The term "soma" derives from a stimulant drink used in ancient Aryan (Indo-Iranian) rituals, in particular those of Vedic India. Soma was a ritual drink of importance among these cultures, and is frequently mentioned in the

Rig Veda, which contains many hymns praising its energizing and intoxicating qualities.

In both Indian and Iranian tradition, the drink is identified with the plant, and also personified as a god, the three forming a religious or mythological unity. The plant is the god and the drink is the god and the plant is the drink — they are all three the same. Soma is similar to Greek ambrosia; it is what the gods drink, and what made them deities. Mortals also drink it, giving them access to the divine.

Soma was apparently prepared by pressing juice from the stalks of a certain mountain plant. The plant probably grew in the homeland of the Indo-Iranians, possibly the Hindu Kush, but the migration of the Aryans into the Punjab region removed them from the area of its occurrence, and it had to be imported. In the

Rig Veda, soma was described as growing in far-away mountains and had to be purchased from traveling traders. Later, knowledge of the plant was lost altogether, and Indian rituals reflect this in expiatory prayers apologizing to the gods for the use of a substitute plant (rhubarb) because soma had become unavailable.

There has been much speculation as to what was the original soma plant. Although it was generally assumed to be hallucinogenic, soma was also associated with the warrior-god Indra and appears to have been drunk before battle. So it might also have been a stimulant. For these reasons, energizing plants as well as hallucinogenic plants are among the candidates that have been suggested.

Several mushrooms have been suggested, including

Amanita muscaria (fly agaric or toadstool) and the psylocybin-containing

Stropharia cubensis. The mushroom theory is supported by later Tibetan legends connected with urine drinking, and it is indeed possible that in Tibet, the shamanistic practice of eating psychedelic mushrooms, and subsequently drinking the urine of the one who has taken the mushroom, still containing much of the agent substance, has been connected with Vedic terminology surrounding soma.

The Tibetan word for “cannabis” is derived from the Sanskrit

soma-raja ("king Soma") and cannabis has also been suggested as a soma candidate based on the Tibetan evidence. The choice of cannabis is further supported by the traditional Zulu use of this drug for energizing warriors.

The most likely non-hallucinogenic, stimulant candidate plant is a species of the genus Ephedra, shrubs with numerous green or yellowish stems growing in mountainous regions. The native name for Ephedra in most Indo-Iranian languages of Central Asia is derived from

soma- (e.g., Nepali

somalata).

Archeological excavations have found ceramic bowls yielding traces of both Ephedra and cannabis, and Ephedra and the pollen of poppies. These finds support the theory that the soma plant was Ephedra, and the soma drink was a composite comprising Ephedra and cannabis or opium.

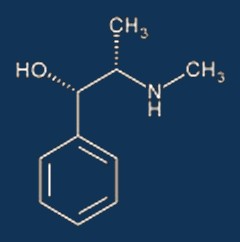

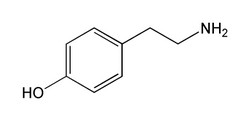

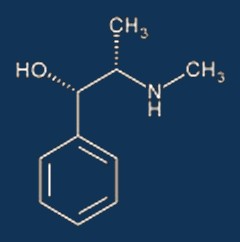

Ephedrine, the primary active substance, is an alkaloid with a chemical structure similar to amphetamines. Ephedrine results in high blood-pressure and has a stimulating effect more potent than that of caffeine. It is still used in Iranian folk medicine, and the traditional Chinese herb

Ma Huang, used in the treatment of asthma and bronchitis for centuries, contains ephedrine as its principal active constituent. Anecdotal reports have suggested that ephedrine helps thinking or studying to a greater extent than caffeine. Some students and some white-collar workers have used ephedrine (or ephedra-containing herbal supplements) for this purpose, as well as some professional athletes and weightlifters.

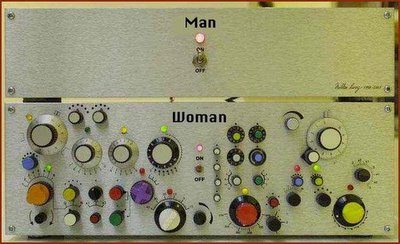

Ephedrine molecules occur as two "mirror images," or isomers, much like a pair of hands. The very potent (-) isomer mimics the effects of adrenaline and is responsible for the amphetamine-like stimulation characteristic of Ephedra products. The (+) isomer, also known as pseudoephedrine, is far less potent as a stimulant. However, it retains much of ephedrine's ability to open airways and nasal passages. For this reason, pseudoephedrine is marketed as a decongestant, such as Sudafed.

Pseudoephedrine works by stimulating receptors (alpha-receptors) in certain areas of the body, particularly in the lining of the nose and sinuses. Pseudoephedrine shows greater selectivity for the nose and sinuses and a lower affinity for the central nervous system than other Ephedra alkaloids. When the alpha-receptors present in the walls of blood vessels are stimulated by pseudoephedrine, the vessels contract and narrow. In the lining of the nose and sinuses, this results in less fluid being pushed out of the blood vessels into these linings. This reduces the production of mucous, thereby relieving the symptoms of nasal congestion. Other beneficial effects include increasing the opening of obstructed Eustachian tubes. Pseudoephedrine is also used as first-line therapy of priapism, a painful and potentially harmful medical condition in which an erection does not return to its flaccid state.

Pseudoephedrine should not be used by anyone who has taken monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) within 14 days or who intends to take such a medication in the next 14 days. It’s a really, really bad idea to take pseudoephedine and MAOIs and eat

mistletoe berries at the same time.

The similarity in chemical structure to the amphetamines has made pseudoephedrine a sought-after chemical ingredient in the illegal manufacture of methamphetamine. In an attempt to inhibit meth production, federal law prohibits buying cold preparations containing pseudoephedrine in quantities greater than 3 packages in any 24-hour period.

Due to the current methamphetamine epidemic, Georgia law now requires that pseudoephedrines such as Sudafed be removed from the shelves of pharmacies and supermarkets and stocked behind the counter to prevent people from buying (or stealing) mass quantities of the drug. In essence, the bill placed Sudafed in a class of drugs somewhere between "Rx only" and OTC. The funny thing about this legislation is that despite being put behind the pharmacy counters, sales of Sudafed have remained strong. And last I heard, the meth epidemic in Georgia has not ended.

As I blogged last

March 23, I have been taking Sudafed on a daily basis since early 2004 to clear chronic sinus congestion. Once I learned that the behind-the-counter legislation was pending, I started stocking up on Sudafed, buying the maximum-allowable two packages every time I went to the supermarket or drugstore. However, my stockpile has since been depleted, and now I am forced to go to the pharmacy, wait at the prescription check-out line, and request the drug by name in order to purchase it. It is a good opportunity to observe the practice of the

kshanti paramita (the perfection of patience).

On December 15, 2005, Senators Jim Talent (R Missouri) and Dianne Feinstein (D California) attached a strict "anti-meth" bill to the latest iteration of the refuses-to-die Patriot Act. On top of making Sudafed a behind-the-counter drug in the entire US, the new legislation would require the purchaser to show a photo ID and sign a purchase log to allow a pharmacy to track how much they've purchased. How store-hopping would be prevented is not identified in the proposed amendment, but one disturbing possibility would be data-basing and tracking Sudafed consumption.

If the legislation is removed from the Patriot Act, or if the Patriot Act doesn't make it through the Senate, Talent and Feinstein have vowed to attach it to another bill at some point down the road. Their legislation, another example of compromising civil liberties for the illusion of “safety,” will do nothing to stop the meth epidemic in the United States and will only serve to frustrate consumers, make law enforcement agents out of pharmacy personnel, and further erode American freedom, while letting legislators take credit for doing “something” about the meth situation.

Pfizer, the manufacturuer of Sudafed,

spent $12 million trying to develop additives for Sudafed that might make it harder to remove the pseudoephedrine it contains. They abandoned the project in 2003, seven years after announcing its existence. In late 2004, Pfizer publicly disclosed its plans to make available a new OTC product, Sudafed PE, which does not include pseudoephedrine. Sudafed PE contains a different decongestant called phenylephrine in a formulation sold for years in Europe. The new product became available on January 10, 2005. Sudafed products which combine the decongestant with other ingredients will be completely converted to phenylephrine later in 2005, though original Sudafed will still be offered.

So let’s review what we’ve covered here: Aldous Huxley, the Vedic scriptures, psylocybin mushrooms, Tibetan ritual urine drinking, Zulu cannabis use, traditional Chinese medicine, non-stop erections, mistletoe, alpha receptors, the methamphetamine epidemic, my Sudafed stockpile, the Patriot Act and the

kshanti paramita. Next I may have to blog about the dangers of web surfing while ingesting too much caffeine.

In these times of rampaging fundamentalism, with its emphasis on “moral values,” creationism and the blurring of the line between Church and State, it’s refreshing to see that Victoria’s Secret has managed to make an industry out of selling sensuality in the suburbs. Any time I’m in a mall, their store is always chock full of soccer moms, brides-to-be and teenage girls buying lacy bras, stockings and garters, and thongs.

In these times of rampaging fundamentalism, with its emphasis on “moral values,” creationism and the blurring of the line between Church and State, it’s refreshing to see that Victoria’s Secret has managed to make an industry out of selling sensuality in the suburbs. Any time I’m in a mall, their store is always chock full of soccer moms, brides-to-be and teenage girls buying lacy bras, stockings and garters, and thongs.

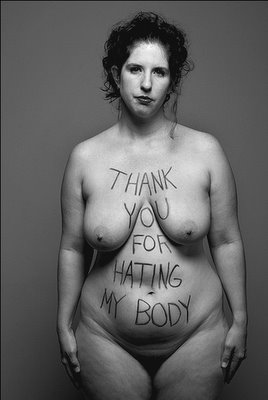

Erotica, on the other hand, depicts the sexual and sensual and presents it is a way that engages the heart and mind, raising the energy from the lower to the middle and upper chakras. The best erotica turns you on, but also makes you aware of more than just your arousal. Some artists, such as Robert Mapplethorpe, can tease us by simultaneously drawing the energy both ways and cause one to consider the conflicting emotional distinctions in novel ways.

Erotica, on the other hand, depicts the sexual and sensual and presents it is a way that engages the heart and mind, raising the energy from the lower to the middle and upper chakras. The best erotica turns you on, but also makes you aware of more than just your arousal. Some artists, such as Robert Mapplethorpe, can tease us by simultaneously drawing the energy both ways and cause one to consider the conflicting emotional distinctions in novel ways.  I’m not sure this posting has anything to do with Zen, although I did try to bring it up a few times. Maybe I’m just writing this as an alibi to post some nekkid pictures on my blog.

I’m not sure this posting has anything to do with Zen, although I did try to bring it up a few times. Maybe I’m just writing this as an alibi to post some nekkid pictures on my blog.